NJDOT WITTPENN BRIDGE PROJECT – HISTORICAL INFORMATION

Hackensack River Lift Bridges

New Jersey Railroad Bergen Cut

Pennsylvania Railroad Harsimus Branch Bridge

PRE-HISTORIC CONDITIONS

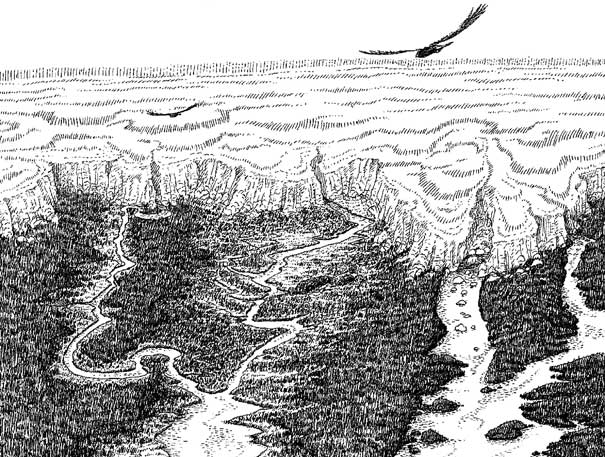

Artists depiction of the Meadowlands region at the time of the glacier’s retreat, more than 12,000 years ago. Illustration by John Quinn from his book, Fields of Sun and Grass.

The Meadowlands region was formed by the Wisconsin Glacier about 20,000 years ago. The glacier stretched all the way to Perth Amboy. When the ice sheet began to melt and retreat, it gouged out the area between what is now the Palisades and the ridge along Schuyler Avenue. It also formed a deep freshwater lake now known as Glacial Lake Hackensack.

Approximately 10,000 years ago, the lake breached at the glacier’s end in Perth Amboy and began to drain, and the Hackensack River was created. After many centuries of rising sea levels, the river was exposed to the tides of the Atlantic Ocean, forming the Hackensack River estuary.

At the time of the earliest known human presence in the Mid-Atlantic region 10,500 years ago, sea level was approximately 80 feet lower than today. The Atlantic shoreline was 40 miles to the east of its present location. The Meadowlands was a broad, forested valley crossed by numerous, meandering, freshwater streams.

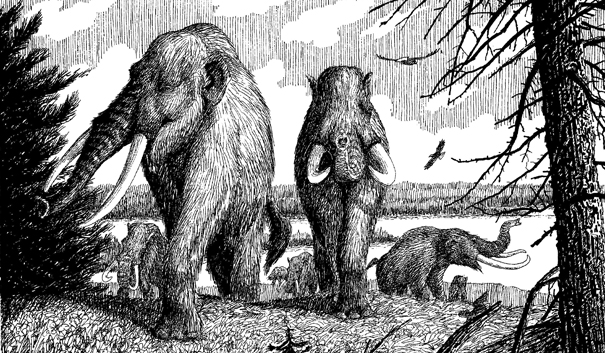

From about 8,000 to 3,000 years ago, a warmer climate changed the Meadowlands’ environment. The region was covered by forests of American larch and black spruce.

Artist depiction of mastodons along Glacial Lake Hackensack, roughly 11,000 years ago. Illustration by John Quinn from his book, Fields of Sun and Grass.

Native Americans became less nomadic and gradually established permanent settlements in the upland regions bordering the Meadowlands and the Hackensack River estuary. Food and clothing were obtained by hunting, fishing, and gathering. Reeds, clay, and forest provided the basic materials needed to make baskets, mats, nets, pottery, and canoes. Archeologists seem to agree that the Meadowlands was used significantly in the prehistoric period, although scant evidence has been recovered. Though Native Americans farmed and hunted, their low-intensity use of the Meadowlands did not significantly alter its appearance or physical condition.

Atlantic White Cedar forests once covered as much as a third of the Meadowlands. This recent photo of a stand of White Cedars in the New Jersey Pinelands shows what parts of North Jersey likely looked like before the arrival of European settlers.

The forested valley of mixed hardwoods was inundated about 1,000 years ago when sea level rose to near present-day levels following the retreat of the last glacier in the Wisconsin age. The Meadowlands was flooded, and the Atlantic white cedar replaced the larch and spruce. The cedar swamps were the prevailing habitat type until deforestation by the Dutch and English colonists through land expansion projects, fire, lumbering, diking and ditching.

Studies of dated pollen cores found beneath the soil established the Meadowlands as a constantly changing environment. Modern marsh grasses have been found in the area for only a few hundred years.

HISTORIC PERIOD

The historic period, beginning with the European settlement in the 17th century, centered on two related land-use themes:

1) Exploitation through resource extraction: The appearance of European settlers resulted in attempts to alter the Meadowlands through land expansion and development.

2) The development of transportation networks: From the 17th century, the Meadowlands has been a significant part of the major transportation networks that deliver resources from the region’s interior to the international ports lining New York Harbor.

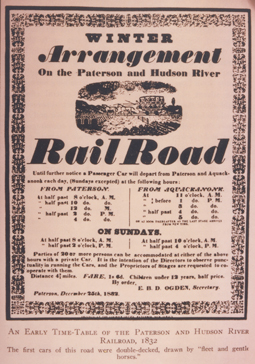

Beginning with the early turnpikes and railroads, which led to ferries on the Hudson River, and continuing with today’s highways and railways leading to international air and sea ports on both sides of the Hudson River and over bridges and under tunnels to New York City, the culture, history and economy of the Meadowlands have been intimately tied to the development of local and regional transportation systems.

SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES

The early Dutch and English settlements were concentrated to the East of the Meadowlands District along the Hudson River and to the south of the District along Newark Bay and the Raritan River. Bergen and Paulus Hook were the first areas of European settlement in the immediate vicinity of the District. They were colonized in the 1620s and 1630s and are now part of Jersey City. Conflicts between the Native Americans and the European settlers resulted in the destruction of some Dutch settlements and harsh reprisals against the Native Americans.

As a result of the Dutch and Indian wars, the fortified Town of Bergen was settled in 1655 and incorporated in 1668. The citizens of Bergen are believed to have controlled huge plantations that extended into the meadows, the beginnings of attempts to exploit land in the District through agriculture.

The Meadowlands was originally part of several land patents. Among these patents were:

• The New Barbados Patent, purchased by William Sanford in 1668, included 10,000 acres of meadow in the current towns of Kearny, Lyndhurst, North Arlington and Rutherford.

• The Berry Patent, purchased in 1669, included the areas of East Rutherford, Carlstadt, Moonachie and Little Ferry.

• The Secaucus Patent, purchased in 1663, by New Amsterdam (New York) Governor Peter Stuyvesant.

The subdividing of these early patents in the late 17th and 18th centuries resulted in settlement taking place in the higher ground surrounding the Hackensack River basin. Early towns included Bergen (Jersey City), Hackensack, Newark and Acquackanonk (Passaic). These towns were inhabited primarily by Dutch settlers from Manhattan and Long Island, except for Newark, which was settled by the English from Connecticut.

The growth of these small towns resulted in the exploitation of the natural resources in the valley below, along the shores of the Hackensack River. A continued series of land grants and subdivisions extended from the earlier lots near Penhorn Creek north to Cromakill Creek along the eastern edge of the District in what is now Secaucus.

The Europeans constructed permanent settlements, harvested crops, grazed livestock, and built roads and bridges. The early economic activities of fishing, hunting, farming and harvesting of salt hay, marsh grass and cedars slowly gave way to industrial and manufacturing uses such as milling, tanning, copper mining and clay mining (for brick production).

Boats likely provided the main form of transportation in the early years of European settlement due to the location of settlements along the major rivers and the difficulty in crossing the meadows by foot or by horse. Improved Native American trails provided some overland routes.

NINETEENTH CENTURY

Little Ferry was one of the largest brick producers in the world, exporting bricks down the Hackensack River to cities in the Northeast. Courtesy of Little Ferry Historical Society.

The 19th century was marked by the introduction of road and rail networks across the Meadowlands, the establishment of historic settlements on high ground, the operation of mills and clay mines, and land reclamation activities.

Meadowlands communities continued to grow as more jobs were created and communities around the region developed into commerce centers.

The mid-1800s saw residential development in present day Carlstadt, Little Ferry, North Arlington and municipalities surrounding the Meadowlands. Little Ferry was developed as a ferry crossing along the route from Hackensack to Bergen. The construction of the Bergen Turnpike in 1804 resulted in the eventual replacement of the ferry crossing with a bridge in 1828.

The Morris Canal opened in 1831, providing a transportation route from the Delaware River to the Passaic River. By 1836, the canal was extended to the Hudson River. In the vicinity of the Meadowlands, the canal followed the course of the Newark Turnpike across the marsh at what is now Kearny before heading south.

Much of the historic development in the Meadowlands has been a product of the turnpikes constructed in the first quarter of the 19th century. These roads, along with water transport, were a vital link in the colonization of the area by allowing farm produce, lumber, copper, brick and other locally produced products to reach the New York and European markets. The roads to Schuyler’s mine in North Arlington and to Newark were improved during this time and became the Belleville and Newark Turnpikes, respectively.

Paterson Plank Road was built across the marsh at this time, providing a direct route from Paterson to Jersey City via Acquackanonk. Paterson Plank Road was considered a product of the “plank road fever” of the mid-19th century. These roads were constructed of cedar planks about three inches thick, laid side-by-side to a width of approximately 8 or 9 feet.

The “plank road fever” was eventually quieted by high maintenance costs and competition from more cost-efficient canals and railroads. Some of these dirt and cedar plank roads have remained in their original locations, becoming the present-day Paterson Plank Road and the Belleville, Newark-Jersey City, and Bergen turnpikes.

Population growth in Meadowlands communities, together with the technological advances of the Industrial Revolution, fueled the development of passenger rail service through the District. Rail service, in turn, allowed people to live farther away from their places of employment. The rail lines, originally used to transport freight, included such present-day lines as the West Shore, Main, Boonton, and Morris and Essex lines. The lower land costs and proximity to New York City led to the development of several rail yards in the Meadowlands.

The 19th century also brought considerable development to Secaucus, particularly Snake Hill. The Snake Hill area covers 152 acres, bordering the east bank of the Hackensack River. According to some accounts, early colonists named the area Snake Hill because its marshland was infested with black water snakes, many 12 to 15 feet long. Snake Hill also may have been named after Jacob Schneck, who owned the property in the 1860s.

There are historic accounts of Native American occupation on or adjacent to the hill. Snake Hill was part of the Pinhorne Plantation, which was the center of the village of Secaucus from about 1680 into the 19th century. Penhorn Creek, at the eastern boundary of Secaucus, was named after William Pinhorne, with few aware of the original, correct spelling of the name. The site was later used as an encampment and lookout during the Revolutionary War and served as the location for various public institutions from the Civil War era to the beginning of the 20th century. These included a penitentiary, an alms house, a tuberculosis sanatorium and an asylum for the insane.

It has been said that in the 1890s an advertising agent passing by Snake Hill in a passenger train was inspired by the outcropping hill of rock. Soon photographs of the Rock of Gibraltar, which had a similar profile, were being used in advertisements for the Prudential Insurance Company of America. The image of the rock remains synonymous with Prudential to this day. Since the early 1900s, the area became known as Laurel Hill. Today, the site is home to Laurel Hill County Park.

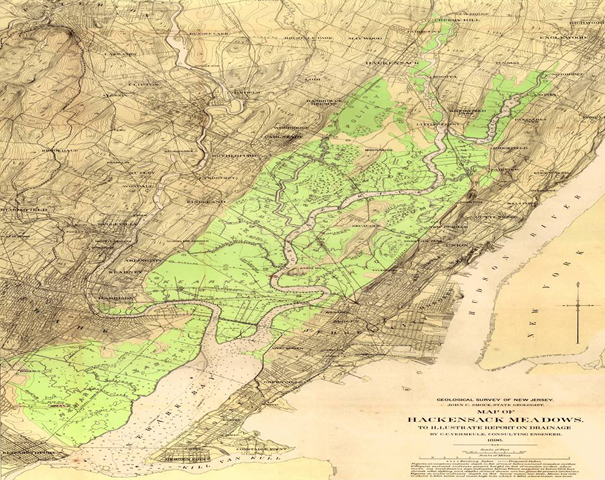

Throughout the 19th century, efforts at land reclamation took the form of early dikes, sluiceways and networks of drainage ditches throughout the District. The earliest recorded attempt to “reclaim” the Meadowlands actually dates back to the end of the 17th century, when Major Nathaniel Kingsland drained part of the marshlands in the vicinity of Kearny and Harrison by means of a sluice gate. Presumably placed across the mouth of Kingsland Creek, the sluice gate produced land for grazing. The Swartwout brothers attempted the first large-scale reclamation project in 1816 by draining and diking some 4,200 acres in Hudson County. The project succeeded in embanking 1,300 acres that produced vegetables, flax and hemp. Damage from high tides and muskrat burrowing soon resulted in the flooding of the reclaimed land. The Swartwouts abandoned their attempt by the 1840s.

In 1867, Spenser Driggs and Samuel Pike devised a reclamation plan that involved building stronger, iron-cored or plated dikes to prevent damage from the tides and the muskrat population. Several miles of these dikes were constructed in the meadows, including locations along the Sawmill and Kingsland creeks. Although the project was successful in diking nearly 4,000 acres, the crops grown on the land reportedly failed. Partly as a result of an agricultural depression in the 1870s, financial support was withdrawn following Pike’s death in 1872.

After the failures of the various land reclamation projects, the Meadowlands remained a vast, largely vacant tract of land between the urban New York City and the developed, but more suburban areas to the north and west. Individual pockets of settlements generally centered on industries located at the edge of the meadows.

TWENTIETH CENTURY

The early 20th Century brought the internal combustion engine and the development of the automobile and trucking industries. Land that was once used for agriculture was redeveloped for new roadways and expanding rail yards, which led to the growth of the warehouse and distribution industries. Perhaps the biggest impact on the Meadowlands District was the construction of the New Jersey Turnpike, extending the length of the District along two corridors on either side of the Hackensack River.

By World War II, most upland areas surrounding the meadows were fully developed. Land reclamation was again attempted in the early 20th Century by the Bergen County Mosquito Control Commission. About 17,000 acres of meadows were drained, mainly through the construction of ditches. Lands previously used for grazing and the harvesting of salt hay became islands of industrial and suburban growth, transportation corridors and extensive landfills.

These landfills were the biggest change to the face of the Meadowlands. For years, unregulated dumping of solid waste took place in the District, with extensive filling of wetlands with no oversight. A study in 1970 identified 51 landfills in the District. Dumping practices at the time were “dump and push” operations, where trucks would dump and push loads on top of other loads or push the fill over the edge.

The Hackensack Meadowlands Development Commission was created in 1969 by the Hackensack Meadowlands Development and Reclamation Act (N.J.S.A. 13:17-1 et seq.) – the agency was renamed the New Jersey Meadowlands Commission (NJMC) in 2001. In February of 2015, the New Jersey Meadowlands Commission was made a part of the New Jersey Sports and Exposition Authority (NJSEA). At the time of the NJMC’s formation, regulation of landfills was just beginning. A survey of waste going into the District in 1969, conducted by the State Department of Health (the predecessor of the state Department of Environmental Protection), showed that more than 5,000 tons were brought into the Meadowlands every day, six days a week, 300 days a year, from 118 New Jersey municipalities.

Perhaps the most important initial role of the NJMC was to regulate acres of open landfills that had been operating without any kind of oversight for years. These unregulated landfills had a drastic impact on the Meadowlands ecosystem – uncontrolled pollution and lack of wastewater treatment harmed the birds, fish, mammals and other wildlife that had once been abundant in the Meadowlands.

As the zoning and planning authority for the Meadowlands District, the MC created the region’s first Master Plan, which in addition providing for the sanitary disposal of solid waste, also set a blueprint for the orderly development of the region, and the protection of the delicate balance of nature. The NJMC has worked hard to carry out its mandates. The landfills were cleaned, development occurred where appropriate and more than 3,500 acres of environmentally sensitive wetlands have been protected. As a result, the Meadowlands District today is an environmental jewel teeming with wildlife and an economic engine spurred by commercial and industrial development. Billions of dollars in development now occupy once fallow land. Today, there are no operating landfills in the Meadowlands District.

TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY – ENVIRONMENTAL AND ECONOMIC TURNAROUND

The NJSEA has made great strides in its commitment to guiding orderly development. The Commission has adopted several redevelopment plans that aim to bring about economic growth by transforming underutilized and abandoned properties into thriving homes for industry. These include the Kingsland Redevelopment Plan in Lyndhurst, Rutherford, North Arlington and Kearny; the Secaucus Transit Village Redevelopment Plan; the Koppers Coke Redevelopment Plan in Kearny; and the Teterboro/Industrial Avenue Redevelopment Plan. In addition, the NJSEA reviews its rules and regulations on an ongoing basis to find areas where common-sense changes can reduce the cost of doing business.

In addition, the NJSEA’s tireless efforts have helped attract billions of dollars in new development to the area over the past 40 years, and the Commission has invested tens of millions more in infrastructure improvements that have benefited District municipalities, residents and businesses. Once written off as a land of unregulated landfills and pollution, the Meadowlands is also now experiencing an environmental renaissance thanks to the conservation efforts made over the years. The NJSEA has preserved thousands of acres of environmentally sensitive wetlands and conducted numerous scientific studies that have helped bring about environmental revitalization and wildlife re-emergence in the District and improvement of water quality in the Hackensack River.

Today, more than 280 species of birds are seen in the Meadowlands, including 34 on the New Jersey endangered, threatened and species of special concern list. Simultaneously, the NJSEA has preserved thousands of acres of environmentally sensitive wetlands and conducted numerous scientific studies that have helped bring about environmental revitalization and wildlife re-emergence in the District and improvement of water quality in the Hackensack River. The NJSEA’s efforts in this area have led to the establishment of the Meadowlands District as a premier ecotourism destination. The Meadowlands District includes 20 parks, several providing access points for waterfront recreation. The NJSEA offers pontoon boat and canoe tours and guided nature walks to give visitors an up-close view of the environmental renaissance.

The NJSEA has also become a regional leader in the promotion of renewable energy. The NJSEA built the first solar farm on a State-owned landfill, an innovative approach to finding a productive use for a landfill that had been closed for 30 years. The 3-megawatt installation, now operated by PSE&G at the NJSEA 1A Landfill in Kearny, includes 12,506 photovoltaic panels mounted on 13 acres atop the 35-acre landfill that supply electricity directly to the electric grid. The Authority has also built a 120-kilowatt solar carport canopy built over its administration building parking lot in DeKorte Park. The 504 solar panels on the canopy provide approximately 20 percent of the electricity needs of the Commission’s headquarters.

As the planning and zoning authority for the Meadowlands District, the NJSEA remains committed to building upon the solid foundation that has been set for economic growth and environmental revitalization in the region.